Today I want to talk briefly about critique.

As writers, critique is part of what we do. Instead of avoiding it or dreading it, I believe we can learn to embrace it. It’s not always going to be pleasant, but after having edited hundreds of books and worked with as many authors, I strongly believe that the ability to ask for and accept constructive critique is one of if not the mark of a good writer.

I’ve talked in the past about how to critique, but now we’ll discuss accepting critique. I obviously cannot speak for anyone else, but here are three things that I think are important to keep in mind when you are preparing to receive a critique of your writing:

1. Have an Open Mind

If you aren’t entering the critiquing process with an open mind, then what’s the point of even asking someone for a critique in the first place? Anything they say to you will be automatically dismissed, and you will have wasted both your time and theirs. Being open to the possibility of revision will allow you to, at the very least, consider an alternative view even if you ultimately decide not to take it (see #3).

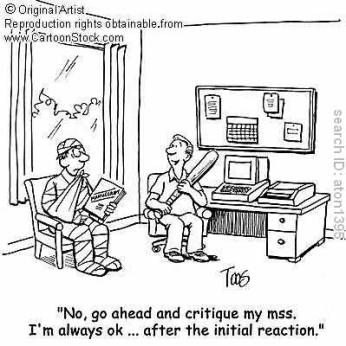

2. Don’t Take it Personally

This one is hard.

After all, this is your baby. The product of uncounted hours staring at a blinking cursor when you could have been watching Bones on Netflix or baking an apple pie from scratch. But the thing is, the person offering critique is only trying to help you. This is, of course, assuming you’ve chosen a worthy critique partner or beta reader.

If that’s the case, then this person is not out to hurt you intentionally. They are not out to destroy your self-esteem or writing career. They truly want you to succeed, and they want your writing to find success; and so you must understand that this is not personal. If you feel like it might get personal, maybe that’s a sign you should find a new reviewer (i.e., not your mom).

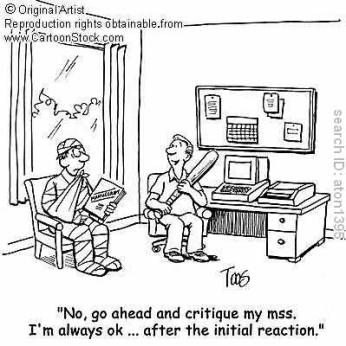

3. Realize that You Don’t Have to Take Their Suggestions

In most cases, you will not be forced to take a critiquer’s suggestions. If your book comes back with a suggestion to remove a certain scene or phase out a character or use a different point of view but YOU feel strongly that it should stay in, then keep it! Your critique partner/beta reader/editor isn’t always going to make a suggestion you want to follow, and realizing that you don’t have to should take some weight off your shoulders. Now, obviously this isn’t an excuse for not changing anything. Remember to keep an open mind (see #1).

But let’s say you have a favorite scene–one you think is hilarious and well written–and the reviewer came back and said he or she didn’t like the scene. That doesn’t mean you have to cut it, but maybe you should consider revising. Maybe the point isn’t coming across how you intended, isn’t reading in their head how it reads in your head. Or, it could be that reviewer just didn’t get it, and it’s fine how it is.

Asking for critique doesn’t mean you will be forced into changing something you don’t want to change. But if you are keeping an open mind, it may be a good opportunity to rework a good scene into one that’s great.

_________

I know there are more tips and tricks for critique, but those are a few that I’ve found to be helpful, both as one who has received critique and one who has given it. Now I’d like to hear from you!

How do you learn to embrace critique?